Agricultural

bureaucrats make time for her

and the mute gweilo.

The third member of the Rice Harmony group that I hung out with was Eshya. She’s an environmental scientist by trade, but her job here goes far beyond the usual science and engineering aspects of environmental management. She’s conducting research on the government’s agricultural policies, while spending time with farmers in the village to understand better how their current farming methods mesh with their way of life.

Here we are – me, Eshya and Shu Hao, on our way to the local town in the back of a sort-of-motorised rickshaw:

Eshya decided to capitalise on my visit, and dragged me along to a set of meetings with bureaucrats in the local government agriculture offices. She wanted to find out what the government pest control recommendations are for rice farmers. Sometimes it’s difficult for ordinary people to get access to government workers, and Eshya’s hunch was that the spectacle of having a foreigner along for the meetings might be helpful.

And it was! Well, I didn’t actually do anything, but I believe I was a useful prop. All I did was sit there drinking endless cups of tea and smiling serenely, and handing out my university business card to all and sundry, while Eshya had four meetings with Serious and Important Looking Men in charge of agricultural administration.

One of the tips that Eshya got from these meetings was to go visit an agricultural supplies shop in one of the nearby villages. So we went down there. Here she is talking with the proprietor:

Her method is a bit like a “mystery shopper” – she presents as a customer, and describes the particular problem she’s having with her rice crop (some sort of bug infestation). She then asks what the government recommends as a response to this problem.

In the above photo, you can see Eshya looking at a piece of paper the shopkeeper has handed her. That paper has the government recommendations in simple terms. Basically, farmers are advised to use this or that pesticide depending on the insect that is bothering them. There aren’t any recommendations about alternative, non-chemical methods of controlling pests.

Eshya told me that this is one of the challenges that she deals with in her job at Rice Harmony. Farmers tend to be very obedient and follow government policy without question. (It’s also significant that the main point of distribution of this policy is in a shop which sells chemical pesticides.)

Eshya sits in the

farmers’ front rooms – sipping tea

and building “guanxi“.

One of the most important things that Eshya does isto spend time with the farmers in the local village. Each night after dinner she checks her list and pays house calls to two or three families. This is a relaxed time of day when the urgency to solve immediate problems is less intense.

I was honoured to be able to accompany Eshya (and Shu Hao) on a few of these visits. (Again this entailed me drinking a lot of tea!). Here she is chatting with some of the farmers who have taken up the challenge of producing rice without harmful pesticides:

One of her aims in these informal conversations is to try and understand, from the farmers’ perspectives, what constrains them from transitioning to less chemical-intensive methods. In many cases it’s labour. From what I could gather, it’s only been since the 1980s that the government has been recommending pesticide and fertilizer use for rice farming.

These farmers still remember a time before that, when the work that the chemicals now do was performed by human yakka. For example, hauling bulky manure and compost requires more heavy lifting than spraying a concentrated soluble fertiliser. So the advent of chemical farming was something of a relief in what is a very labour-intensive occupation.

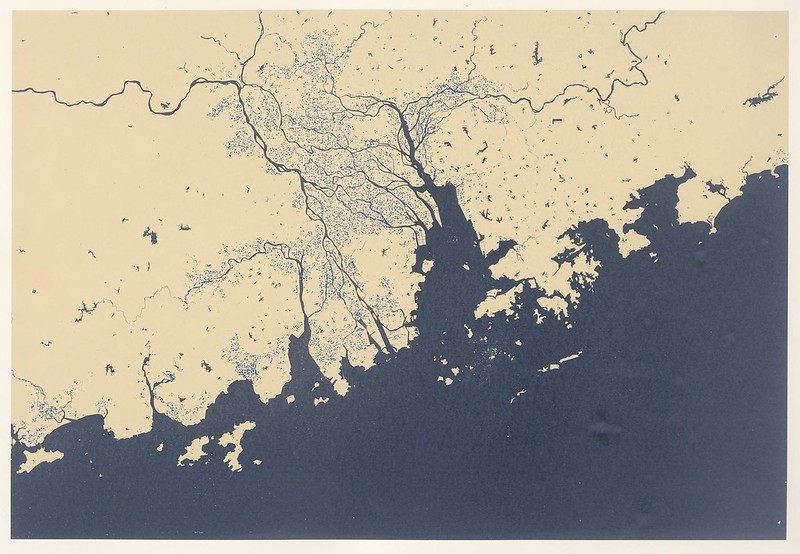

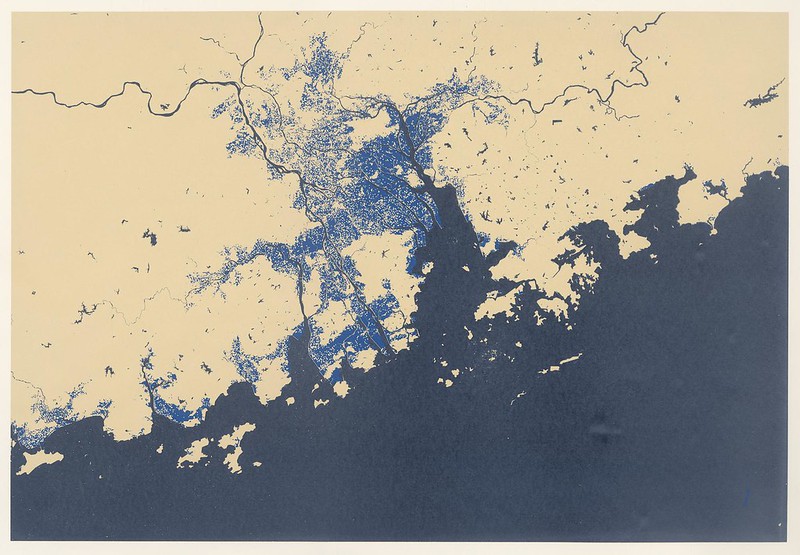

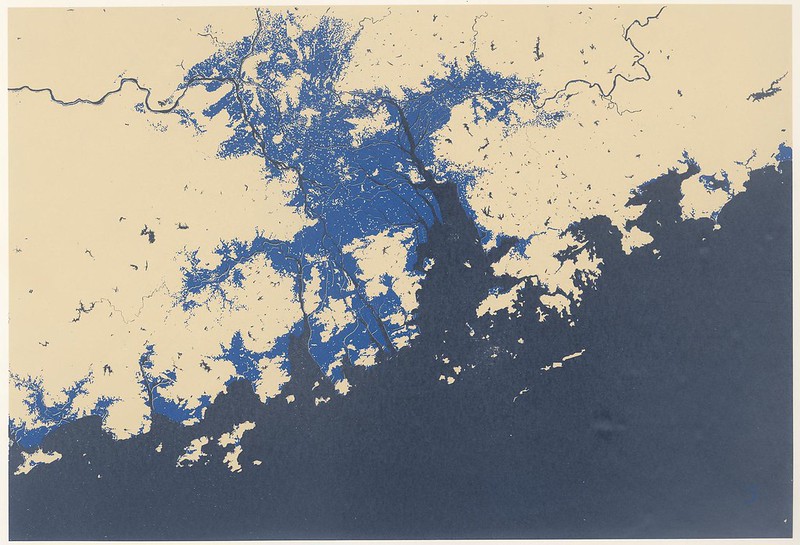

On top of this, the current farming generation is ageing. The children of farming families from the village now have the opportunity to travel to the big city to study. There are so many diverse (and better paid) career paths available to them, and so they don’t tend to return to the farm. When their parents retire, they sometimes follow the kids to the city – and so the village starts to empty out.

This is one of the complex problems facing farming in China today. Nobody that I spoke to seemed to have an easy solution. Farming is simply too laborious, and too low-paid, to be attractive to the younger generation. Who will grow the rice in the future? Will China become a net-importer of rice from other, poorer countries?

I’m familiar with some of these social problems associated with farming. In Australia, the economics of farming have tended towards fewer farms, much larger farms, and more mechanisation. This can results in social and geographical isolation, and the depopulation of rural centres.

Eshya and I talked about all these problems, and I showed her the work I’d done previously with Ian Milliss on The Yeomans Project, as well as its successor Sugar vs the Reef. We were excited about the crossovers in the work of Rice Harmony and in my creative arts approach. I do hope that we have a chance to share strategies again – perhaps via the Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation, which is also grappling with very similar issues around regional culture, environmental management, and agriculture.

“Eshya and the Farmers” is one of three blog posts about my visit to Xiangyang Village in Guangdong.

In the first post, I spend time with Linda in the mud of the rice fields. In the second post, I hang out with ShuHao and go looking for bugs and frogs.

This adventure in the rice paddies was brought to you by Guangzhou Delta Haiku.